>> Triple A: Urban Legend

>> Letter from the Editors

More...

Two members of the Ninth Art editorial board - Antony Johnston and Alasdair Watson - are confessed Goths, both of whom started reading SANDMAN at school. The third, Andrew Wheeler, read the series only after it was completed, and has never worn eyeliner. The three convened around the drinks cabinet to discuss Neil Gaiman's epic DC Vertigo series SANDMAN.

Now, who ordered the cider and black?

ALASDAIR WATSON: Andrew, let's see if you can get through this one without you mentioning Chris Claremont, OK?

ANDREW WHEELER: So, Chris Claremont, when he started writing SANDMAN... Oh, OK. According to the inside indicia, it's been five years since THE WAKE was collected, which means the SANDMAN library was completed five years ago.

ANTONY JOHNSTON: Is that all? It feels like so much longer.

WATSON: Five years is quite a long period of time. Quite a lot has happened to me in those five years and I'm assuming I'm not alone in that.

WHEELER: No, it was just you. Our lives were static.

JOHNSTON: I was already working at that point.

WHEELER: You mean you were reading SANDMAN and you weren't a student? Gasp!

JOHNSTON: I did start reading it when I was in sixth form. And I always associate it with my student days.

WHEELER: Because it's studenty. That's the first thing we can say about SANDMAN. The first defining keyword is studenty.

WATSON: "Look how literate I am."

WHEELER: It's for people who smoke clove cigarettes and ponce about.

JOHNSTON: Oh no, please. That's going a bit far. It's for people who read books. A hell of a lot of books. And sit around and have debates on the merits of literature, like we're doing now.

JOHNSTON: Oh no, please. That's going a bit far. It's for people who read books. A hell of a lot of books. And sit around and have debates on the merits of literature, like we're doing now.

WHEELER: We have penetrated the fourth wall.

WATSON: And the fourth wall is screaming rape.

JOHNSTON: It's the thinking man's comic book, in a way.

WATSON: No, I think it's the thinking eighteen-year-old's comic book.

WHEELER: I was having drinks with Larry Hama in a Texan bar in new York - this is how all my stories start...

JOHNSTON: Did you drop this? There appears to be a name on the floor.

WHEELER: Anyway, I asked him who his favourite comic creator was, and he said Carl Barks was his number one - the guy who created Uncle Scrooge. I asked if he rated Neil Gaiman, and as I recall, he said no, he can't write comics. He can write stories but he can't write comics. This is some years ago, so I may not be quoting him exactly right.

JOHNSTON: I'll defend Gaiman against that. I don't think that's true. He's not a master of the form - a craftsmen in the same way that someone like Moore is - and there's no doubt that the skill of Gaiman's collaborators is extremely influential on how good his comics work is. But I don't think that it's true at all to say that he can't write comics. There are quite a few points in SANDMAN that play up to the visual strengths of comics extremely well

WATSON: There's that one page in BRIEF LIVES where Delirium's recounting the story, and as she's recounting it her appearance shifts to what it was in the various points in the story.

JOHNSTON: There's his timing, as well. Timing in comics is an extremely difficult thing to get right, and his timing is exemplary from panel to panel. His dramatic pauses or points of change are extremely well done.

WATSON: As I recall, one of the things Larry Hama doesn't like - you've told me this story before...

WHEELER: It's my only story. It's a bit sad isn't it?

WATSON: I know. It's the fact that I hear it three times a day, it becomes a bit wearing.

WHEELER: Although Chris Claremont once scowled at me - oops! Sorry.

JOHNSTON: "Fifty years ago, I was in a bar with Larry Hama..."

WATSON: But SANDMAN is talking head comics, and if I recall correctly, Larry doesn't feel that's very clever. I think there are points in SANDMAN where it very much is talking heads. I'm thinking particularly of "Calliope", the one the script is included for. I remember when I was reading the script, I was thinking, "This is doing nothing that he probably couldn't have done better in prose".

'The written script is almost a better telling of the story than the comic is.' JOHNSTON: Well, he could probably do it as well, but not necessarily better. You could make the same argument about half of PREACHER. I don't think there's any reason comics shouldn't be talking heads.

WATSON: But Calliope is not a visual story. There is maybe one moment in it that's a really strong visual image, and even then the description of it in the prose has almost as much impact.

JOHNSTON: Yeah but it's the medium he's chosen to work in. Did you ever see Alan Bennett's TALKING HEADS on television? It was people talking to a camera.

WATSON: But as much as anything those were designed to show off the skill of the actor.

JOHNSTON: Well, you could say the talking heads issues of SANDMAN are there to show off the skills of the artist.

WATSON: The artist for calliope, Kelley Jones, is not someone I would have picked for a talking heads piece.

JOHNSTON: That's probably not Gaiman's fault. I agree, Kelley Jones is not someone I would have picked for a talking heads comic, but you're not always in control of these things are you? He knew who the artist was - he addressed the script to Kelley - but that doesn't mean if it had been, I don't know, Charles Vess, that the letter wouldn't have started 'Hey Charles' and the script would have been more or less the same. You hear that a lot, that criticism that someone's not doing something that couldn't be done in another medium, but you could say that about three quarters of the work in any medium.

WATSON: Yes, but the written script is almost a better telling of the story than the comic version was.

JOHNSTON: Do you not think that's because Gaiman is a decent writer, and therefore can make his scripts interesting?

WATSON: I'm reasonably sure that's true, but at the same time, what's in that Calliope piece that plays to the strengths of comics?

JOHNSTON: Not playing to the strengths doesn't necessarily mean that it shouldn't be done in that medium. Like I say, three quarters of the work in any medium could be done in another medium, but it doesn't make it better, doesn't necessarily make it worse. It's only really powerful or genius work that can only be effective in one medium. I don't think it's fair to expect 75 issues of SANDMAN to be genius the whole way through.

WATSON: The disappointing thing, though, is that you've got sequences like SEASONS OF MIST, BRIEF LIVES, the huge spread in WORLD'S END, that have really strong visuals. If he's capable of doing that, and he very clearly is, why is it missing at other points in the story?

JOHNSTON: Surely for the same reason that when you watch a film you may get the occasional bit of photographic brilliance, with a landscape shot or a tracking shot or something like that, but when you've got three people sitting around the dining room table, enjoying a meal, you don't necessarily get feats of acrobatics from the cameramen.

WATSON: No, but perhaps a TV series is a better comparison. A film is a whole story in itself. But each issue of a series should have, to my mind, a certain amount of the whole thing. If you look at something like BUFFY, for example, it lost its way recently because its played each episode as subservient to the whole, rather than letting each episode stand on its own.

WHEELER: But I think Gaiman does fall into that trap. One of the things about SANDMAN that I think is remarkable and that made it significant is that it's a long-form series that is structured, but it's so structured that once in a while you do just get a building block. Whole arcs, sometimes - THE KINDLY ONES just feels like one big structural inevitability, rather than a piece of art. There's all these strands being pulled together, and I don't think it's a good story, it loses its way.

WHEELER: But I think Gaiman does fall into that trap. One of the things about SANDMAN that I think is remarkable and that made it significant is that it's a long-form series that is structured, but it's so structured that once in a while you do just get a building block. Whole arcs, sometimes - THE KINDLY ONES just feels like one big structural inevitability, rather than a piece of art. There's all these strands being pulled together, and I don't think it's a good story, it loses its way.

JOHNSTON: The funny thing is, I didn't enjoy THE KINDLY ONES at the time, but I've recently re-read it, and thoroughly enjoyed it as a whole piece. SANDMAN as a whole reads better as trades.

WHEELER: Yes, because SANDMAN was a pioneer in that regard, and that's why it grabbed people's imaginations, more than because it was particularly genius. Which is not to say it wasn't solid storytelling, but on reflection, placed in the context of other works, I don't think it stands out as strongly now that it's just one of the long-form stories in comics, all of which have weaknesses.

WATSON: I think it's a bit hard for me to judge that, because SANDMAN is still the one that I will come back to. And I can only think of two of the long-forms that are currently out and completed - SANDMAN and PREACHER.

JOHNSTON: But you admit that that's partly nostalgia on your part?

WATSON: There are a few of those SANDMAN collections that I really like. SEASONS OF MIST is very solidly in my top comic stories of all time. It's generally the one that everyone says is their favourite.

WHEELER: I think I've re-read the trades of 100 BULLETS more than I've re-read any SANDMAN trades.

WATSON: You don't own any SANDMAN trades, though.

WHEELER: No, but I've had the opportunity. I've read it all the way through twice. There are bits of it that I enjoy very much, and that's the reason I went back and read it a second time, to find those bits.

WATSON: Which bits were the ones you liked?

WHEELER: Um... I did like the story with the girl travelling around her childhood fantasy world. The Cuckoo. Which I think everyone else hates. And I like the Corinthian.

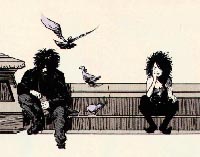

JOHNSTON: What about the story where Death takes Dream on a tour of all her duties? "The Sound Of Her Wings."

WHEELER: That was a good story. I was always interested in Destruction as a character, so I liked when that was resolved. I liked Distant Mirrors, the four stories collected in FABLES AND REFLECTIONS. Especially Ramadan.

JOHNSTON: I would never try to claim that SANDMAN is without its faults. It does have weaknesses. But I think most of those can be attributed to the fact that at the time it was not then the norm for a comic to start and then a) be collected into book form very quickly and b) be conceived as a finite series. Gaiman himself has said that he was desperately trying to find his way for the first nine or ten issues. Whereas these days, in the case of something like 100 BULLETS, Azzarello can go into that thinking, well, there's probably going to be a trade after about four or six issues, and I can run this for five years and wrap it up. That's acceptable.

WHEELER: SANDMAN has conditioned the Vertigo reader, to that extent. SANDMAN is to hold up or blame for the trade programme mentality that kills books like MINX and OUTLAW NATION.

JOHNSTON: Which is a shame, but I think overall that was a good progression to make. It's a shift that I support.

'THE KINDLY ONES feels like a structural inevitability rather than a piece of art.' WATSON: You were saying Gaiman was floundering for his first eight or nine issues before an ending occurred to him. While Ennis has never said he was floundering at the start of PREACHER, I recall an interview with him where he said, 'I knew I wanted PREACHER to end, but it wasn't until issue ten or so that I knew how it ended'.

JOHNSTON: I don't think that's too much of a surprise or too unusual if you're working on a long-form series. Andrew, you've talked about the good bits, what are the bad bits?

WHEELER: I can't really... as a whole work it's not something I want to read again from beginning to end. I know there are people who regard it with nostalgic fondness, but equally there are people who are quite severe detractors. I'm not one of them, but I do see their point, and I always worry when something gets a cult attachment to it where it means that people become blind to the baggage.

WATSON: I do remember hearing one person say, "I bought my Death T-shirt because I'm a good little sandboy".

WHEELER: The cult of SANDMAN lives on, and the spin-offs live on. It's Vertigo's Spidey books.

WATSON: To be fair I'm looking forward to the collection of Endless stories that's due out.

JOHNSTON: I'm not that fussed about that, but I'm enjoying LUCIFER still. I was just going to say, actually, I'm kind of between the two of you. I have a great nostalgic fondness for SANDMAN, but these days I just tend to go in and read bits, because I know there are weak issues. I know the first eight or nine issues are very poor in relation to some of what came up after, and I don't tend to read those much at all.

WATSON: With the first nine issues he was trying to cross over with as many people as possible to boost the sales.

WHEELER: I think the chief weakness is not any one particular story. I think what people criticise it for most is the goth posturing and the 'look at all the books I've read' aspect, and I do think Gaiman's guilty of that. He's very articulate and literate, but the posturing reeks off the page.

JOHNSTON: I agree with you, to an extent, but I don't think you can blame him for the people that read it. Just because that sort of thing was picked up on and happens to appeal to your hand-stapled-to-forehead goth types who stand in the corner and read poetry, I don't think you can blame him for that.

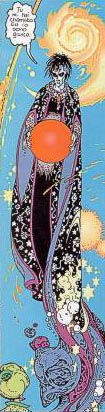

WHEELER: Is he not a goth? Surely you don't write SANDMAN if you're not a goth? He created that world in his own image.

JOHNSTON: Oh god yes. Of course he's a goth. But Warren Ellis is a goth, and you don't see people standing around quoting poetry from his books.

WHEELER: Is he a goth?

WATSON: You're joking? This is a man who listens to acts like Danielle Dax and Big Black.

JOHNSTON: Like most of the goths his age. So I don't think it's fair to blame Gaiman for the fans. It's like Marilyn Manson. His fans are arseholes, but you can't blame him for that.

WATSON: Hey!

WHEELER: The Neil Gaiman/Marilyn Manson fan is getting uppity.

WATSON: I only own two Marilyn Manson albums.

WATSON: I only own two Marilyn Manson albums.

JOHNSTON: Only? OK, goths, literature, quoting. Gaiman does do it a lot.

WHEELER: Yes, SANDMAN is full of quotes. This is not the fan's fault that he's gesticulating about how clever he is.

JOHNSTON: Or how well-read he is. I don't think there's anything wrong with that. Yes it's pompous, but that doesn't make it bad.

WHEELER: But I can't enjoy a story if it feels like a lot of footnotes strung together. That's a problem for me.

JOHNSTON: But I think there is still a very strong narrative running through it. Even when he's at his most literature-quoting, there is still a story that he's telling.

WHEELER: There is. Although I don't think the story ends well, to be honest. Something he has in common with Shakespeare - he can't write endings.

JOHNSTON:I admit, I really liked the ending of SANDMAN. It's inevitable. It's the only way it could have ended.

WHEELER: That's what disappoints me, in a way.

JOHNSTON: I think that's the mark of a great story. If you can't actually see it in advance, but at the end you think, of course, nothing else could have fitted, I think that's the mark of a great story.

WATSON: I don't like the ending, mostly because it makes me want to strap on some large boots and kick Morpheus to death.

WHEELER: He is a twattish lead character.

WATSON: Yes. It's apparent throughout that he's a big berk. But the whole, 'Oh, I must die now because it is noble' ending makes me want to kill things.

WHEELER: He's a twat who always wins, apart from the fact that he dies, and even when he dies he wins.

JOHNSTON: Do we have to like our protagonists?

WHEELER: If I dislike them and they win, then I'm not going to get a sense of reward from the story. It was pointed out, for example, during the publicity tour for OCEAN'S ELEVEN that the people you're cheering on are all criminals, and what they're doing in the film is committing a crime. And yet you're still cheering them on, and that's because the characters are all likeable and the character they're ripping off is a casino owner, and everyone wants to see the casino owner get his.

JOHNSTON: But that's being roguish rather than nasty.

WHEELER: Yeah, but roguish just means that your bad qualities are tempered with good ones. Morpheus's bad qualities needed to be tempered with some good ones. And they weren't, he was just pompous and a bit of an arsehole.

'I don't think you can blame Gaiman for the people that read SANDMAN.' WATSON: You could make an alternative reading of SANDMAN to play to his good qualities, but all of his good acts take place off panel. And he's not usually a bad or an unpleasant person, but he has a sense of duty to his responsibilities, whatever they might be.

JOHNSTON: How about the fact that he realises and attempts to affect the fact that he has to change and adapt? Because it's made quite clear that this is obviously something that is not congenital to his nature, and it is a struggle presented throughout the whole story that he's never had to change, and suddenly he has to adapt, show compassion, et cetera.

WHEELER: The decision to seek redemption is not in itself a virtue, it's simply a survival trait. I don't think it makes you virtuous to want to get out of prison.

WATSON: The Christian right is going to be stoning our website.

JOHNSTON: I'm not necessarily talking about virtue, I'm talking about tempering bad qualities with good. I think he does have a few good qualities, he's just a bit crap about putting them into effect.

WHEELER: Yes, he's deeply socially inept. That's got to be one of his major problems.

JOHNSTON: There are many sympathetic characters in literature and fiction who are so bound to their duty that all other considerations are secondary. He's like the hard working cop whose marriages always fail. It's a terrible analogy, but that's exactly what it's like.

WHEELER: The difference is, I never felt he was in service to someone else, I always felt he was the maker of his own service. He wasn't keeping his house for his master, he was keeping his house for himself. He had a tremendous sense of duty that he instilled in his staff, so that they would continue to serve him well. That's not the same as being a cop on the beat.

JOHNSTON: It is stated several times that The Endless have no master, but they all have duties.

WHEELER: But Destruction abandons his duty. Which is the exact reference that's held up as a contrast. He can stop, he doesn't have that excuse. And Destruction is the heart of the book as far as I'm concerned. He's the likeable character.

WATSON: But Destruction abandons his realm and says, now destruction happens randomly. If anything is going to happen randomly, destruction's a good choice. I'm not sure I'd want to dream at random. God forbid I should end up with someone else's dreams.

WHEELER: You'd get used to it.

JOHNSTON: All in all, I still stand by SANDMAN as a great work. I don't think it's unfair to say it's revolutionary in terms of the medium. But I will admit that it has its faults.

WATSON: I still stand by about 50% of it as my favourite comics ever.

WHEELER: Is it a top ten comic of all time?

WATSON: Bits of it.

JOHNSTON: I think so. It's in there.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.