>> Triple A: Urban Legend

>> Letter from the Editors

More...

JOHNSTON: Within all storytelling media there are elements that are unique to that medium. Things in films which can only be done with moving pictures. Things on stage that can only be achieved on stage; things in novels that can only be done in prose. What is there in comics? What is there that's unique to the form in terms of storytelling mechanics and tricks?

WHEELER: The last panel of every page. I hate to say this after our last discussion, but it was Larry Hama who first alerted me to this...

WATSON: You have replaced Chris Claremont in your affections.

JOHNSTON: I'm going to ban any mention of Larry Hama.

WHEELER: I'm actually going successively through everyone who wrote WOLVERINE. So eventually I'll get on to Frank Tieri. He'll become my idol. Some writers believe that you have to structure your story so that every last panel is a page turner. Some people believe in it religiously, and it's not always the best writers that do, perhaps because they use it as a crutch. I think it was something Stan Lee believed in very strongly.

JOHNSTON: Regardless of whether or not you believe that, it is a tool that's unique to the medium.

WHEELER: I don't think it's something creators should need to do on every page. I think that can interfere with the story and upset the flow. You can't punctuate a story that rhythmically.

JOHNSTON: Well, like any tool you shouldn't use it if there's no reason to. OK, that's definitely one. What else is there?

WATSON: Time. The media you mentioned, things like theatre, cinema - when you're watching something happen, barring weird speed effects, it happens at one second per second. In prose it takes you as long to read it as it takes the writer to describe it. In comics it's possible to stretch and bend time by altering the layout of the page, altering the shape of the panels. You can get a splash page that's either a really fast action page or a long frozen moment, just in the suggestion of the art. It's only in comics that there is that elasticity of time, that reliance on the reader to provide the time, and therefore the ability to give them subtle cues - or even miscue them as to how long something is taking.

JOHNSTON: True. Even when you get the repetition of panel or very slow movement from panel to panel in something like DARK KNIGHT RETURNS, it's still not the same as watching something in slow motion.

WATSON: The one that springs to mind for me - although it's a device that's used an awful lot - is TRANSMET, where you've got a panel that is exactly the same as the one before it, but silent. And then it cuts on to the next panel - which may even be the same panel again, but with speech - and that moment is a beat.

JOHNSTON: That's a very common device, though I think maybe that's intended to emulate film, rather than being unique to comics.

WATSON: It depends. If you shape that silent panel differently to the other panels around it, you get a very different effect.

WHEELER: I think, the way that time is used in comics, it's often trying to emulate film. It's rarely trying to emulate real life. It's trying to emulate the way in which filmed stories - television or cinema - are told. And that's not a criticism, I think that's just a reality of how we understand time's structure in narrative. Creators have to model it on something, so instead of real life, they tend to model it on the way a director would cut a scene.

WHEELER: I think, the way that time is used in comics, it's often trying to emulate film. It's rarely trying to emulate real life. It's trying to emulate the way in which filmed stories - television or cinema - are told. And that's not a criticism, I think that's just a reality of how we understand time's structure in narrative. Creators have to model it on something, so instead of real life, they tend to model it on the way a director would cut a scene.

JOHNSTON: Although I do personally think that something like the parent shooting scene in DARK KNIGHT, where he's having that flashback and you see things like the string of pearls flying through the air, I think that's much more effective than, say, a slow motion flashback in a film would be. Witness the first BATMAN movie, in fact, which replicated that scene extremely faithfully, and was nowhere near as effective. And I think that is mainly due to the power of the frozen image, and the fact that you can move around between these images, especially when they're presented in a grid, the way Miller did them.

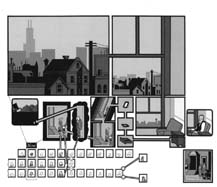

WATSON: One of the things about DARK KNIGHT, even with those sixteen panel grids, there's quite a lot of white space. Imagine that without the white space. In DARK KNIGHT you have these frozen moments - you're seeing everything in super detail, because it's all running in slow motion. Cut the white space out and what you've got is a series of really static images.

WHEELER: To use time that effectively in comics I think you need to have a tremendous rapport between the writer and the artist. Which is why the people who are best known for it are writer-artists like Frank Miller and Scott McCloud.

WATSON: Well, the writer needs to be able to convey to the artist the effect he's going for.

WHEELER: But often - sadly, the way the industry works - the writer won't know their artist well, or won't even know who the artist is going to be - and I don't think you can communicate well with an unknown artist. You can go into tremendous detail, but unless you know who it is and understand them a little bit, I think it's going to be tough.

WATSON: But not impossible.

JOHNSTON: If the writer and artist don't know each other it becomes very difficult to get over those sorts of comic-specific effects.

'A splash can be either a fast action page or a long frozen moment.' WHEELER: Ennis and Dillon are an example of a writer-artist team that work together well, but I don't think Ennis uses time as effectively as he could. In the early days of TRANSMETROPOLITAN, Warren Ellis and Darick Robertson established a strong rapport. Alan Moore with the artists on PROMETHEA...

WATSON: I think Alan Moore with anybody...

JOHNSTON: No, that's not true. Have you read SPAWN: BLOODFEUD?

WATSON: I choose not to believe that's Alan Moore.

WHEELER: I think Alan Moore knows when to hand over to his artist. I think with someone like Chris Sprouse he knows he's working with someone who really knows storytelling.

JOHNSTON: And in the case of WATCHMEN, he and Dave Gibbons did literally sit around Moore's kitchen table, talking about it. And you can tell. WATCHMEN throws up another thing that comics do well, which is the use of repetitive visual symbolism. While you get it in television and movies, comic is the only medium in which you can do this and make it so subtle that you sometimes only really notice it when you flip back through the pages.

WHEELER: The other strength of comics that occurred to me, and it's not exactly the same thing, is juxtaposition. The structure in comics is not solely linear. You have the linear and then you have the presentational.

JOHNSTON: You can look at two pictures at the same time, without having to replace one with the other, as you do in a film.

WHEELER: So the story is also... I suppose you could say it's digital and it's analogue at the same time. You've got your linear story, and you've got your digital page, your single unit; the page as a single work.

JOHNSTON: I think that's something that not enough people use effectively, and I think that's maybe because it's quite difficult. Moore is the past master of repetitive symbolism, placing those subtle visual hints, and using them effectively. The tool is there.

WATSON: I'm trying to think who else does it.

WHEELER: Jason Lutes is very good at it. Lutes segues very well. I think a lot of the better artists know to do it but you don't necessarily register it.

WATSON: I think sometimes that might depend on whether the writer is bright enough to give them the cue. "That coffee mug is going to be important later on, make sure it's visible."

JOHNSTON: We should mention Chris Ware's work in relation to time. I don't think there's anyone in modern comics who manipulates time as well as Chris Ware does, especially in JIMMY CORRIGAN, but also in his experimental, tabloid-sized single page pieces that he does.

JOHNSTON: We should mention Chris Ware's work in relation to time. I don't think there's anyone in modern comics who manipulates time as well as Chris Ware does, especially in JIMMY CORRIGAN, but also in his experimental, tabloid-sized single page pieces that he does.

WHEELER: He often breaks the pages down into tiny, tiny panels, often with the same picture over and over again. It sends a very clear message.

JOHNSTON: And with no clear linear way of reading the panels. But if you actually take the time to follow them around, as I have done only a couple of times, you will find that it does all make perfect circular sense. Which is obviously something that would be incredibly difficult to achieve with a moving image. You'd end up with something like LOST HIGHWAY.

WHEELER: Or MEMENTO, which uses structure in a way film usually can't. It has to be an experiment in film, but in comics it's the form.

JOHNSTON: And it doesn't get used enough, I don't think. I think it's interesting that most of the examples I'm thinking of are actually to do with the physicality of the form, the fact that you are looking at pictures on paper rather than moving pictures on a screen, or conjuring pictures in your head from a novel.

WHEELER: It has to be about the physicality of the form, doesn't it? What else do comics offer? The point of comics is that it's the sequential juxtaposition of images...

JOHNSTON: But there's the whole digital comic thing. You can't flip back twenty pages with your thumb, but they're still comics.

WATSON: But imagine WATCHMEN done as a series of image maps, so that when an image recurs you can tab back...

WHEELER: Oh God, I'd hate that. I think that part of the strength of comics is that it is linear at the same time as being digital. You can't get lost - unless you actually don't know how to read comics. People can't follow an overcomplicated narrative, so internet comics could actually stretch things too far by trying to be too experimental. The page works as a restraint.

JOHNSTON: I don't think there's anything wrong with the experimentation in web comics, specifically. You have to experiment to see what works and what doesn't. And I think a lot of people are aware that because they're experimenting, their stuff isn't going to be audience friendly. But that's no reason not to do it. Sometimes experimenting for its own sake is also its own reward. The other thing I was going to mention that made me realise how much this is all tied to the form on paper was that thing J Michael Straczynski did in RISING STARS that was sadly horribly misprinted. Part of the image was on one side of the page and the other was on the reverse, and you had to hold the page to the light to see the whole thing.

JOHNSTON: I don't think there's anything wrong with the experimentation in web comics, specifically. You have to experiment to see what works and what doesn't. And I think a lot of people are aware that because they're experimenting, their stuff isn't going to be audience friendly. But that's no reason not to do it. Sometimes experimenting for its own sake is also its own reward. The other thing I was going to mention that made me realise how much this is all tied to the form on paper was that thing J Michael Straczynski did in RISING STARS that was sadly horribly misprinted. Part of the image was on one side of the page and the other was on the reverse, and you had to hold the page to the light to see the whole thing.

WATSON: It was corrected for the trade, and it was interesting, but I didn't like it.

JOHNSTON: It was very much a gimmick.

WHEELER: It was. I read that trade recently, late at night by the bedside light, and I couldn't see through the page, so I couldn't be bothered with it.

WATSON: In the end I just read the reverse page backwards. I could read mirror writing easier than I could read it by holding it up to the light.

JOHNSTON: That's actually what I ended up doing as well.

WHEELER: The dialogue was purely representative, it wasn't crucial to the plot.

JOHNSTON: It was a clever trick, regardless of how well it worked.

WATSON: It was a clever trick, but it would have seemed like a stroke of genius if it'd had any use. I'm hoping in the third trade there'll be some relevance to those ghosts.

'You've got your linear story, and you've got your digital page...' JOHNSTON: You mean the ghost characters haven't reappeared?

WATSON: No, that was literally a one page stunt.

JOHNSTON: Well, my point is, that was unique to comics. You couldn't do that in any other medium. I wish more people would try to find those elements.

WHEELER: You want people doing Mad magazine fold-ins in their comics? Bring point A to point B?

JOHNSTON: Funnily enough, Chris Ware did those as well. But no, not to those extremes.

WHEELER: John Byrne's SHE-HULK was a great run, because the lead character broke the fourth wall, she knew she was in a comic, and that actually made it a very experimental comic. She would break through the pages so she could get ahead in the story. Byrne was also involved in the ALPHA FLIGHT issue that was all white pages.

WATSON: Oh, two white characters fighting in a blizzard?

WHEELER: Yeah. Snowbird fighting a polar bear, or something ridiculous. And there's... Larry Hama. The silent issue of GI JOE. There is room for experimentation in comics, but experiments aren't a strength of comics. Any medium has its experimental options.

JOHNSTON: Oh, yeah, I'm not saying the things you can do in comics necessarily makes it stronger than any other medium, I just think considering how many tricks and tropes there are that are unique to other media and are used regularly - you can watch a horror movie and watch ten or twelve tricks carried out by the filmmaker that can only be done in a movie - you don't generally spot that in most comics, to the point where we're struggling to think of too many examples. I wish there were more recognised unique tropes, more tools available to storytellers.

'You have to experiment to see what works and what doesn't.' WHEELER: While I would like creators to be aware of the toolbox available to them in comics, I do think people sometimes get too blinded by the idea that comics are something super-special. There's the claim that in comics you can do things that you can't do in other media, but that's not as important as doing what works in comics and telling a good story. People get blindsided by the 'art', and I don't think the art is as important as entertainment - I know that sounds terrible, given the name of the site. But the art is what it is, so why work towards 'art'? Accept that what you're doing is telling a story, and work towards that.

JOHNSTON: I kind of agree with you, but that kind of goes counter to the previous conversation we had, about SANDMAN. What you're saying is that people shouldn't just play to the strengths of the medium for the sake of it; they should concentrate on telling a good story.

WHEELER: I think a creator ought to be able to structure a comic without having to think, 'What can I do to push this beyond?' I think it ought to be more second nature.

JOHNSTON: I think it's perhaps indicative of the infancy of the medium that it's not second nature yet.

WATSON: Well, comics aren't as old as film, but they're only a couple of decades off, and we don't talk about film being still in its infancy.

JOHNSTON: But film was accepted as a valid, mature storytelling medium many years ago.

WHEELER: When did comics start becoming experimental? You have to be experimental to grow, to emerge from that 'infancy', but not every comic has to experiment. A comic should not be judged solely on how artistically innovative it is.

WATSON: No, obviously not. It should be judged on how well it sells!

WHEELER: Yes, so TRANSFORMERS is the greatest comic ever.

JOHNSTON: Or LEFT BEHIND. No, I agree, a comic should not be judged on how innovative it is, but there should be more innovation, more attempt to do things which can only be done in comics. You see it in films all the time, you see it in novels all the time, you don't see it in comics all the time. There are many fine comics that are not experimental. I just wish there were more that were both.

This article is Ideological Freeware. The author grants permission for its reproduction and redistribution by private individuals on condition that the author and source of the article are clearly shown, no charge is made, and the whole article is reproduced intact, including this notice.